J.M.W. Turner and the Sublime Sky

How Turner’s dramatic skies pushed the boundaries of landscape painting and captured the emotional power of nature.

Following John Constable’s careful, observational studies of cumulus clouds and shifting skies, we turn now to his contemporary and rival—Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)—who approached the heavens with a different kind of brush. Where Constable saw clouds as meteorological phenomena to be rendered with truth to nature, Turner saw the sky as a stage for the sublime, a vehicle for emotion, power, and transcendence.

In Turner’s hands, clouds became metaphysical. They were no longer just vapor or weather; they were light, fury, chaos, and divinity. Over the course of his long career, Turner’s skies transformed from detailed atmospheric backgrounds into radiant fields of abstraction, foreshadowing modernism and even impressionism. To understand Turner’s art is to understand his skies, and to understand his skies is to enter a space where nature and the human soul collide.

Turner and the Sublime

Turner was born in London in 1775 and entered the Royal Academy at just 14 years old. From early on, he was interested in landscape—particularly in the emotional resonance of natural forms. Deeply influenced by Edmund Burke’s theory of the sublime, Turner believed that nature, especially in its most violent or awe-inspiring states, could evoke a feeling of overwhelming grandeur that surpassed beauty.

The sky, ever-changing and untouchable, was the perfect subject for this pursuit. Turner’s clouds are rarely placid or picturesque; they boil, shimmer, and blaze. His paintings weren’t meant to simply depict the world—they were crafted to make the viewer feel it.

Scientific Curiosity Meets Spiritual Awe

Though Turner was more of a poet than a scientist, he was not uninterested in contemporary studies of light and weather. He was familiar with Goethe’s color theory, and he observed nature closely during his extensive travels across Britain and Europe. However, his interpretations of the sky were less about accuracy and more about atmosphere—about how light refracts through mist, how clouds part to reveal storms, how color becomes an emotional language.

Where Constable carefully catalogued cloud types, Turner used them as mood itself. His clouds are extensions of the human psyche—stormy, illuminated, shifting between clarity and obscurity. In a way, his paintings anticipated modern ideas of the psychological landscape, where inner turmoil and natural chaos are one and the same.

Notable Works:

To appreciate the centrality of clouds in Turner’s oeuvre, let’s look at three of his paintings, each showcasing a different dimension of his evolving approach to the sky.

1. Snow Storm: Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth (1842)

Oil on canvas, Tate Britain

This is perhaps one of Turner’s most dramatic and controversial works. Legend has it that Turner had himself tied to the mast of a ship during a violent storm in order to directly observe the chaos of nature. Whether the story is true or not, the painting certainly feels like a first-hand experience of elemental fury.

The sky dominates the scene—swirling clouds and waves merge in a vortex of energy and motion. The ship is almost indistinguishable, a ghost swallowed by fog and foam. The clouds aren’t passive background—they are the narrative, the emotion, the sublime terror.

This painting marks Turner’s move toward pure sensation. Detail gives way to abstraction, and the clouds act like brushstrokes of raw experience.

2. The Fighting Temeraire (1839)

Oil on canvas, National Gallery, London

In contrast, this painting is a quieter, more reflective piece, yet its sky plays a profound symbolic role. The painting shows the grand old warship HMS Temeraire being towed to its final berth to be broken up. The sun sets in the background, casting the sky in shades of orange, lavender, and gray.

The clouds in this painting are soft, layered, and tinged with melancholy. The blazing sunset behind them seems to echo the ship’s last moment of glory, with the encroaching dusk suggesting the end of an era. Here, the clouds don’t roar—they weep, gently and with reverence.

It’s a masterclass in using atmospheric light and sky as a metaphor for time, death, and the passage of greatness.

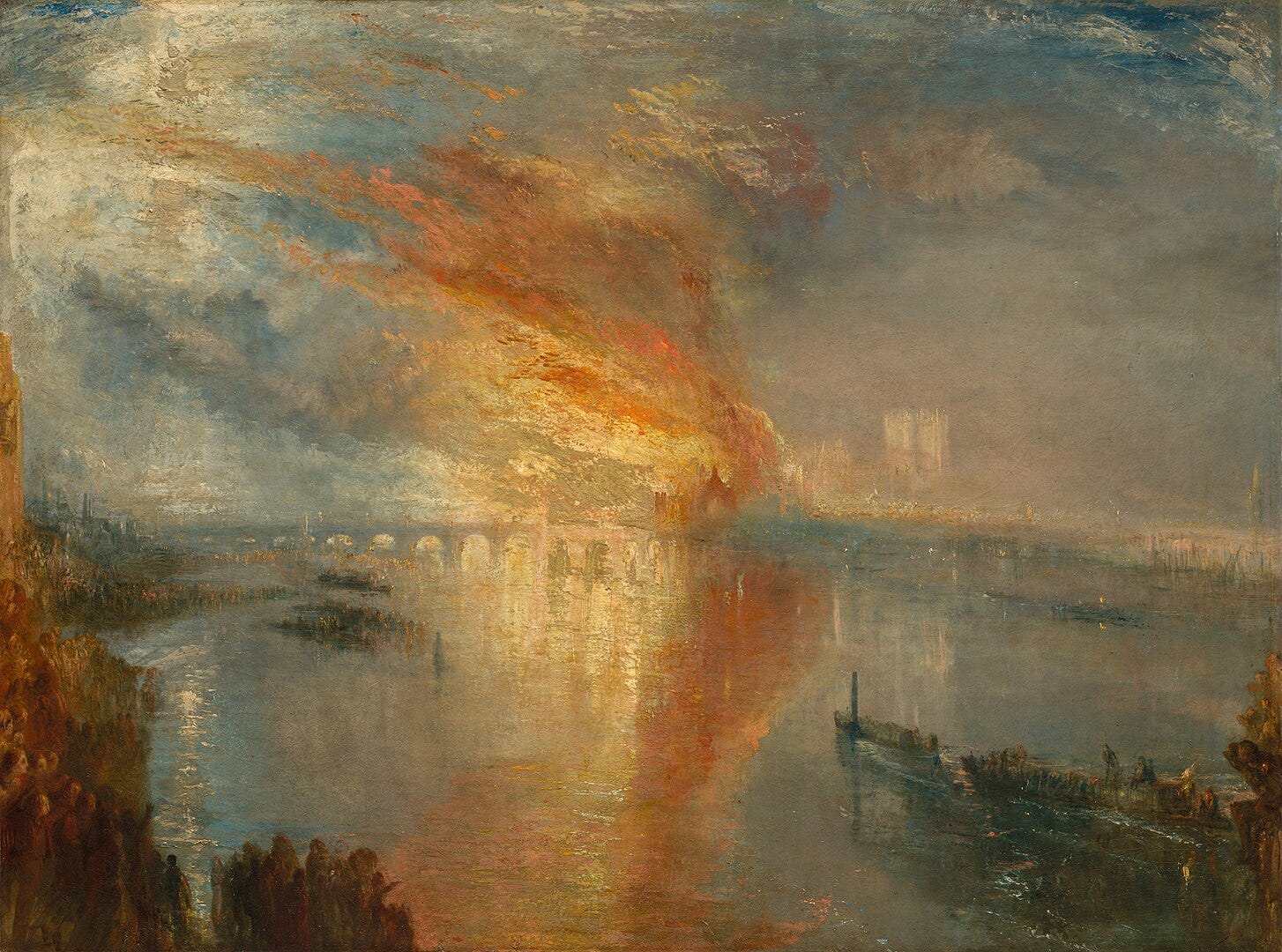

2. The Burning of The Houses of Lord and Commons (1834-1835)

Oil on canvas, Cleveland Museum of Art & Philadelphia Museum of Art.

In this electrifying scene, Turner transforms a real-life event—the fire that engulfed the Houses of Parliament—into a study of light, chaos, and atmospheric spectacle. Flames and smoke rise in vast, luminous plumes, turning the sky into a churning cauldron of golds, reds, and blacks. The skyline disappears into the inferno, blurred by smoke and reflected firelight on the Thames.

As with Snow Storm: Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth, the composition is less about structure than sensation. Both paintings plunge the viewer into a kind of atmospheric vortex, where cloud, wind, light, and motion become indistinguishable. In Snow Storm, it’s wind and sea that threaten to consume the steamship; in The Burning of the Houses, it’s fire and smoke that consume the city. In both, the skies are the real protagonists—wild, disorienting, and emotionally charged.

Both paintings blur the line between subject and setting. But where Snow Storm conveys isolation and struggle against nature, The Burning of the Houses delivers the sublime spectacle of human-made catastrophe. Turner’s clouds—thick with smoke and lit from within—don’t just describe weather, they dramatize it. The sky is alive with panic and awe, as if history itself were burning. In both, Turner dissolves solid form into energy and air, using clouds as the carrier of meaning rather than mere backdrop. The result is overwhelming, visceral, unforgettable.

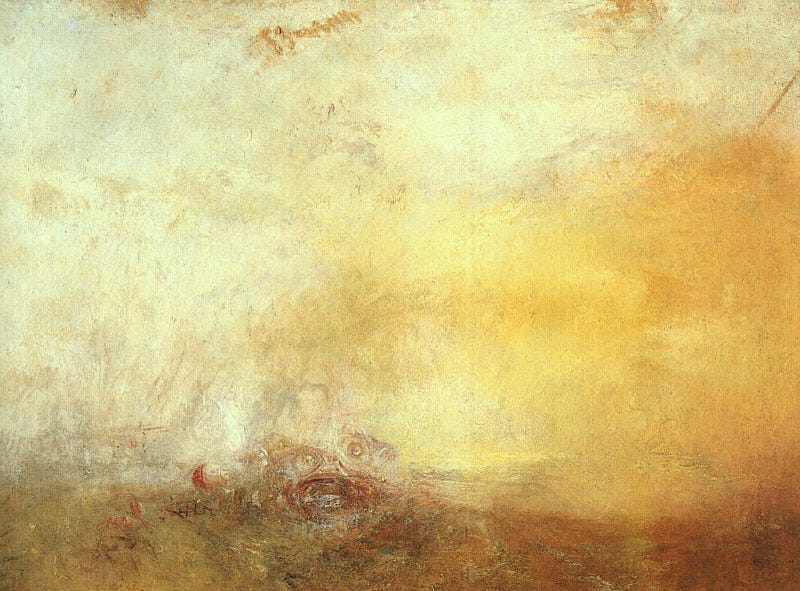

4. Sunrise with Sea Monsters (1842)

Oil on canvas, Tate Britain

One of Turner’s most enigmatic late works, Sunrise with Sea Monsters verges on abstraction. The horizon dissolves into a luminous haze of golds, greens, and violets, as faint organic shapes—possibly dolphins, possibly imagined creatures—emerge from the depths. There’s no clear narrative, no obvious structure—just light, color, and vapor in constant flux.

The clouds here are less formations than forces. They radiate from the rising sun in soft arcs and smudges, like breath on glass. This is Turner unbound, leaning into emotion, atmosphere, and suggestion over detail. His clouds no longer describe—they evoke, drifting into the realm of memory, dream, and the subconscious.

In contrast to works like The Burning of the Houses, where fire and smoke explode across the canvas, Sunrise with Sea Monsters whispers. Its sky is not catastrophic but contemplative, inviting interpretation rather than insisting on it. It’s a painting that rewards feeling more than explanation.

Turner’s treatment of cloud and light here anticipates the looseness of Monet, the spiritual weather of Rothko, and the oceanic dissolves of late Whistler. It marks a turning point—not just in Turner’s own work, but in the very idea of what a sky in painting could be. Less an image of the world than a sensation within it.

Turner’s Legacy in the Sky

Turner’s cloudscapes laid the groundwork for the Impressionists, who took his fascination with light and transience and ran with it. Monet, in particular, cited Turner as a major influence. Even artists like Rothko, who dealt in pure color and mood, owe something to Turner’s abstract skies.

But Turner’s skies weren’t just aesthetic experiments. They were spiritual and emotional truths, painted with a conviction that nature was not outside of us but within us. His clouds weren’t just clouds—they were grief, awe, transformation. In the fleeting shapes of vapor and light, he saw the ephemeral beauty of life itself.

As we continue our journey through artists inspired by the sky, Turner stands as a towering figure—a prophet of the heavens, who gave clouds a soul and made us all look up a little differently.

Want to see more of Turners work?

Check out this pinterest board to explore the breathtaking skies of J.M.W. Turner — a master of atmosphere, light, and emotion in cloud painting.

Next Month: Claude Monet and the Impressionist Sky

If you enjoyed this article and want to receive future deep dives into the art and symbolism of clouds, consider subscribing and sharing The Art of Clouds with fellow sky-gazers.

The Art of Clouds is a monthly newsletter exploring artists throughout history who were inspired by clouds. Each issue sheds light on an artist and their work, uncovering how they captured the sky as a subject and symbol.

Curated by Marc Whitelaw, the artist behind Break Your Crayons.